From Earth to algorithms: Generative AI in geoscience

Generative AI is rapidly reshaping aspects of our lives both at home and in the workplace. Paul Cleverley advocates for the pragmatic adoption of AI tools in geoscience.

© Getty

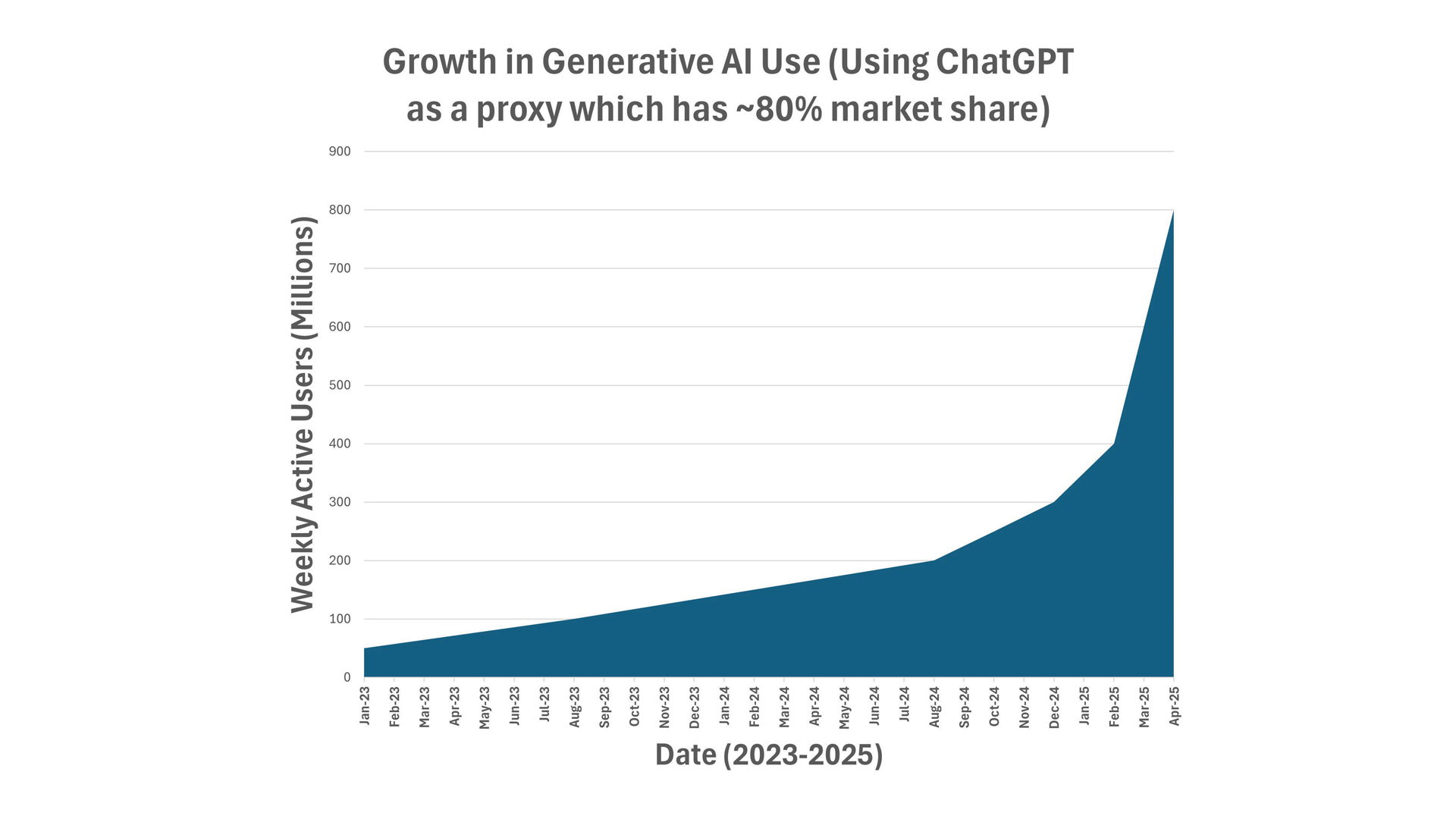

When the generative artificial intelligence (AI) tool or ‘chatbot’ ChatGPT emerged in late 2022 it became the fastest adopted consumer app in human history. With their remarkable ability to answer questions, write emails and essays, summarise concepts or give advice, translate languages, and help with tasks such as brainstorming ideas and coding, such chatbots are now used regularly by one eighth of the world’s online population (Fig. 1).

Excitement about generative AI is tempered by unease. Despite the now widespread and daily use of AI tools (see box ‘AI use in the UK’), concerns around generative AI include privacy, security, quality of outputs, and fake information. Many people also question whether AI could make people less intelligent, negatively impact vulnerable individuals and be used by bad actors to manipulate attitudes.

A dichotomy seems to be appearing, between those who use these AI tools regularly, and those who do not and may be unaware of the possibilities. Here I discuss how geoscientists can use AI tools pragmatically, focusing on AI literacy, technical competency, critical thinking and ethics, and thereby steer a course between hype and negativity.

Figure 1 | Growth in Generative AI use globally since November 2022 (Data source: DemandSage, Sep 2025)

AI use in the UK

In a recent survey, 70% of respondents from the UK stated they had consciously been using AI in their daily lives over the past six months, but only 44% in a professional setting (Brown, 2025). While 38% of UK respondents felt the benefits of AI outweighed the potential negatives (which is lower than the global average of 48%), those aged under 45 were significantly more positive towards AI than those aged over 45.

University undergraduate students in the UK report using Generative AI to: ask questions and explain concepts; identify relevant sources to read on a topic; suggest improvements to a piece of work they have written, and support arguments (Smith, 2025). However, the survey found that almost half of students believe their university’s AI policy has “set out the boundaries for acceptable AI usage but has not actively taught us the skills to use AI well and how to avoid its pitfalls”.

LLMs: The basics

Built from machine learning and often rules-based techniques, AI tools are not intelligent, but they can simulate intelligent-like behaviour for narrowly defined tasks.

Chatbots such as ChatGPT (where GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer) are driven by Large Language Models (LLMs). These LLMs emerged thanks to three forces: web-scale text, computing power, and breakthroughs in architecture (the underlying design) of the model.

The core idea is simple: “You shall know a word by the company it keeps” (Firth, 1957). The LLMs are trained using the vast amounts of text available online (and including all the biases that exist on the internet). The LLM ‘reads’ the text to find patterns in the language (such as words that commonly appear together and grammatical rules) and uses a transformer network (the architecture) to process words in relation to all the others in a sequence. When asked a question or to perform a task, the LLM models the statistical probability of the next word, given the context, to form a response that sounds natural and human-like (hence the name ‘chatbot’).

LLMs are essentially predictive text on a massive scale: rather than finishing one word, they can finish entire paragraphs and essays.

Exercise caution

LLMs can speed up work tasks, surface new data that can reduce uncertainty in our geological models, help explore hypotheses and make new geoscientific discoveries. However, we should always exercise caution.

There are a wide variety of free-to-use and accessible LLMs. The ‘closed’ variety must be used online, while the ‘open’ variety can be downloaded and run locally on your computer. For data privacy and security, we should be cautious about uploading sensitive geoscientific content to web/cloud-hosted AI. Depending on the terms and conditions, inputs and/or outputs may be retained or used to improve models. The legal jurisdiction (i.e., the country or regional laws that apply for data use or if something goes wrong) may allow your data to be used for purposes you did not consent to. Ensure you opt-out of these options where appropriate, or don’t use the AI tool at all if you are uncomfortable with the governing legal jurisdiction.

Almost no LLMs are open source or reproducible. The training data and methods used for training have been kept proprietary and some LLM-based geoscience applications have not released the source code. Be wary of AI tools that are promoted as being ‘open science’ yet have many proprietary elements. This amounts to “open washing” – using the language of openness to gain trust and boost public image, while maintaining control – and can mislead geoscientists about the true accessibility, reproducibility, and scientific value of a tool.

Critical thinking

The geoscientist should always be in the driver’s seat and is liable for any results produced through AI tools.

Prompting (providing questions, guidance, and context to LLMs) is rapidly emerging as a core skill for AI literacy. Two geoscientists, even within the same discipline and using the same LLM, can arrive at very different answers or generate strikingly different insights or results depending on their proficiency with AI tools. The skill is comparable to performing effective Google searches for a literature review but multiplied by an order of magnitude in both complexity and potential. Prompting, therefore, should be recognised not just as a technical trick, but as a foundational literacy for professional geoscience practice in the age of AI.

Generative AI can act as a “Socratic partner”, providing a forum for question-and-answer-based exploration of a topic or problem, and can help us co-create ideas and test hypotheses. These tools can also help refine our writing and reveal errors and contradictions in our work and that of others – support that can be especially helpful for those writing in a language that is not native to them. However, for transparency we should fully disclose, in detail, the use of AI tools in our work, avoiding the ‘cut and paste’ of large chunks of unverified AI-generated text. We should write in our own voice and use our own ideas.

The geoscientist is liable for any results produced through AI tools

It is important to adopt a critical thinking mindset and check outputs so that we do not base decisions on, or disseminate, false information that AI can sometime generate (often termed ‘hallucinations’). Ask yourself, is there an authoritative source for this output and does it support the AI-generated assertions being made? Generative AI can produce outputs that look highly plausible and persuasive, even when they’re completely wrong. While these tools can accelerate research, summarise literature, or spark ideas, they must be used critically. Blindly trusting AI-generated outputs risks introducing errors or reinforcing misconceptions.

There is some evidence that human-AI “teaming” can produce more diverse and innovative ideas (Haarman, 2024). Working together, humans bring creativity, judgment, ethics and context, while the AI tool brings processing power, speed, memory and pattern recognition. However, in some situations, such as the start of a brainstorming or ideation process, it may be better not to use AI at all (such tools could be introduced at later stages). This will ensure that original human ideas aren’t constrained, anchored or biased by the AI’s suggestions, which might lead to an actual reduction of idea diversity (Meincke et al., 2025).

Specialised LLMs

Theoretically, the LLMs that are specialised in geoscience (that is, trained using geoscientific text and data) should always outperform general-purpose LLMs (like ChatGPT) for geoscientific tasks, and many geoscientists may assume they do. The current evidence, however, does not support this.

In some fields, expensive fine-tuned domain-specific LLMs have been quickly surpassed by general-purpose systems like ChatGPT (Li et al., 2023). In the Earth sciences, fine-tuning has shown small accuracy gains (Bhattacharjee et al, 2024), with some larger improvements reported for very narrowly focused applications. However, these geoscience-specific AI tools have not been tested against today’s most powerful LLMs (e.g. GPT-5, Claude 4, Gemini 2.5), which can perform strongly on geoscientific tasks due to the availability of extensive training data. Indeed, some reports suggest that current geoscience-specific LLMs perform worse than state-of-the-art general-purpose LLMs (Dubovik and Suurmeyer, 2024). Baucon and de Carvalho (2024) found that general purpose LLMs (such as ChatGPT) scored 75% on a set of PhD-level geology exam questions.

Current evidence shows that for general geological tasks, freely available general-purpose LLMs combined with smart prompting and retrieval of up-to-date external authoritative geoscience information, are often likely to offer better results than current geoscience-specific LLMs.

Beyond Q&A

LLMs can be used for more than just question-and-answer tasks. Where real data are sparse, LLMs can be used to generate synthetic datasets that can improve the accuracy of model predictions. For example, landslides are generally under reported meaning there are relatively few well-documented case studies globally and thus limited comprehensive data on which to train our predictive models for hazard mitigation. LLMs can be used to generate synthetic datasets for a diverse range of input parameters (such as soil and rock type, slope angle, rainfall etc.) that simulate the causes and conditions for real landslides. Landslide specialists then ‘clean’ the data, filtering out any results that are implausible or don’t make sense. The model is retrained using a mix of real-life and clean synthetic data and analysis has shown that such synthetic data can improve the accuracy of model predictions (Sufi, 2024).

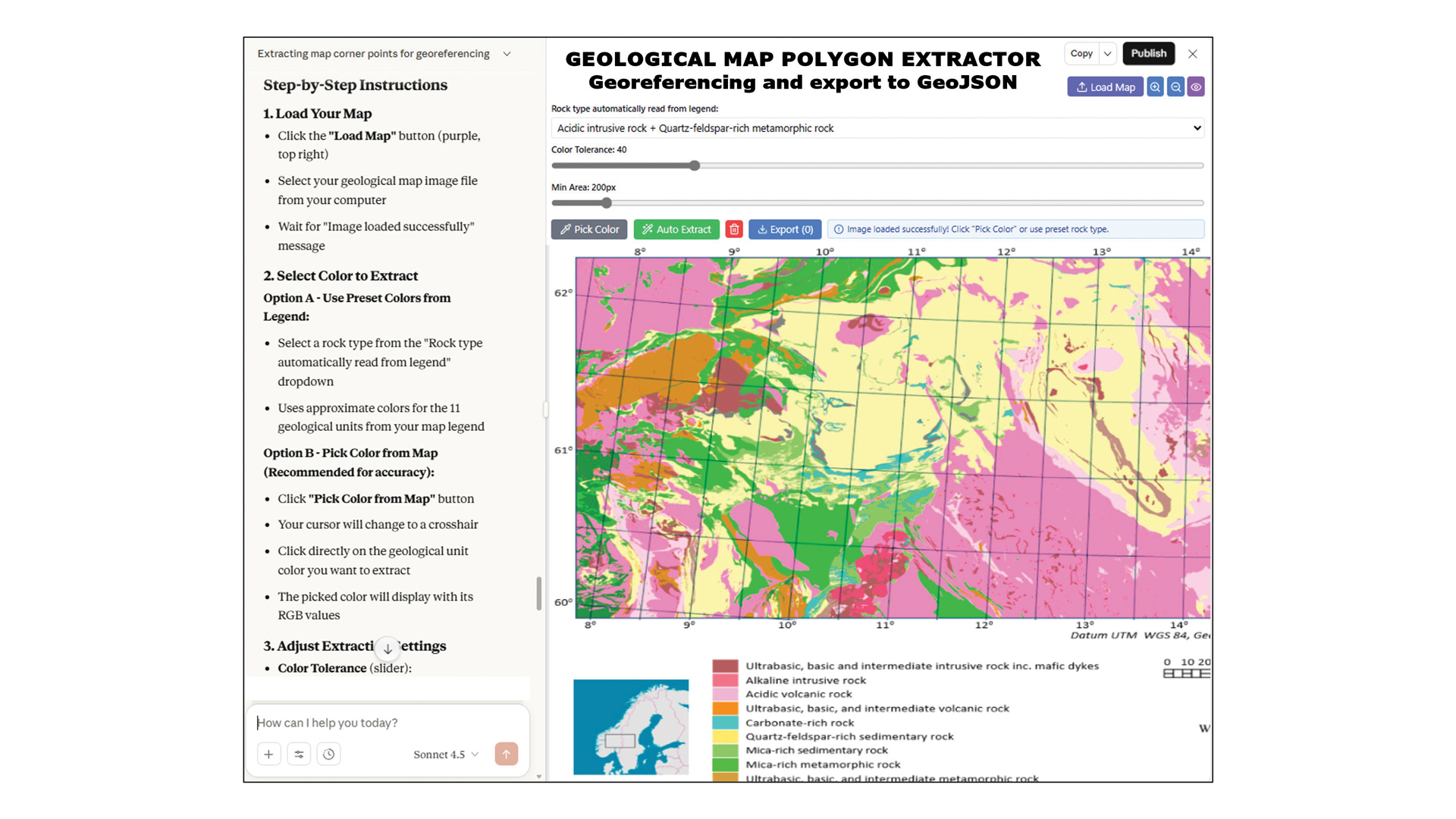

Although requiring careful oversight, LLMs can be used to extract information in context from documents, tables, charts, maps and logs (see figure 2 as an example), thereby automating time-consuming tasks for large volumes of archival content. For instance, orphaned oil and gas wells pose environmental risk, but locating and plugging them can require trawling through vast numbers of inconsistent and outdated historical records, which is a slow and labour-intensive process. Ma and colleagues (2024) showed that LLMs can be used to rapidly and accurately extract data from pdfs record, out-performing conventional approaches for extracting data from well records. A similar approach could support, for example, hydrogeological monitoring, methane emission studies, and the management of other oil and gas legacy assets.

Figure 2 | Automatic georeferencing and polygon data extraction from geological maps. Here I illustrate the use of a general purpose LLM (Claude 4.5 Sonnet) to rapidly create an app that can georeference geological maps and automatically extract polygons to GeoJSON (a geospatial data interchange format) for integration with other data. Map from Erikstad et al. (2022) Multivariate Analysis of Geological Data for Regional Studies of Geodiversity. Resources 11(6), 51. © 2022 Erikstad et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Building applications that use LLMs

With some AI tools and chatbots, the answers and outputs they generate cannot always be accurately linked to their sources, posing a trust issue. To overcome this, we can use LLMs to operate our own tools, access external data sources, interact with structured databases and execute commands – that is, to fetch, transform and analyse data (that are external to the LLM). For example, to lower barriers for people wishing to explore unfamiliar geophysical datasets (such as sea level and wind data), Widlansky and Komar (2025) created a tool that allows researchers to ask questions using everyday language and receive clear explanations and data analyses in response. I created a similar open-source tool, GEOAssist, for use across the geosciences (see box ‘Introducing GEOAssist’)

We can expand an LLM’s problem-solving capabilities to go beyond retrieval

By building applications that use LLMs, we can expand an LLM’s problem-solving capabilities to go beyond retrieval and toward a system that can act autonomously, working to achieve a goal (overseen by the geoscientist). This method can be useful in the geosciences, which are characterised by interdisciplinary teams working with complex and heterogenous data.

For example, Pantiukhin and colleagues (2025) demonstrate how such an approach can facilitate the management and processing of complex data sets using simple, natural language commands, to help detect subtle geological signals of hazard precursors in tectonically active areas. Likewise, Mehmood (2025) used these techniques to turn natural language queries into code for flood mapping, retrieving, processing, and analysing satellite imagery and remote sensing data for disaster risk reduction maps. Yan and colleagues (2025) took this approach further to automate hydrological modelling, parameter setup and simulation from natural language (e.g., “simulate floods for the Little Bighorn basin from 2020 to 2022”). Analyses that usually took weeks to setup, subsequently took hours, with resulting automated reports rated 7 out of 10 by expert hydrologists.

We can also integrate LLMs with our own tools to create Knowledge Graphs – a graph-like representation of things, concepts or objects that are connected by relationships and can be read by both humans and computers. Geoscientists have long presented knowledge and data in graphical forms (such as the geological timescale and geological maps). Using LLMs supported by other techniques, we can generate Knowledge Graphs that represent vast data sets and reveal previously unknown patterns or connections. For example, Knowledge Graphs have been used to predict new mineral associations or geological configurations commonly preceding resource-rich areas. These techniques have yielded new geoscientific discoveries, such as the idea that native copper is more closely associated with oxides and sulphates than with sulphides – an insight not apparent from traditional tables of data. This result, together with broader patterns in copper mineral networks, supports the view that Earth’s oxygenation events drove mineral diversification, particularly the rise of oxidized copper minerals (Morrison et al., 2017).

Using natural language queries, GEOAssist can help with a variety of tasks. Main image, query “Discuss copper porphyry in Zambia”: GEOAssist can crawl the internet for articles, show a histogram of papers downloaded by date, and create an animated plate reconstruction through geological time using GPlates. Left image: Based on pdf documents, GEOAssist can generate a Geoscience Knowledge Graph to aid understanding of the connections and relationships between entities that is also machine readable. Nodes represent entities (such as minerals, rocks, faults, geological processes and periods) that are connected (for example, “mineral X occurs in rock type Y”). The GeoKG links concepts together in a web of relationships, rather than storing information in isolated databases. Right image, query “Show copper, antimony, beryllium and tungsten in Germany”: GEOAssist can collate, assess and map the known copper, antimony, beryllium and tungsten deposits in Germany based on data available via the world’s largest online mineral database and reference resource Mindat. (Image template © Canva)

Introducing GEOAssist

Released in August 2025, GEOAssist (Cleverley, 2025) is a free and fully open-source LLM-based application for geoscientists that can be run locally on your machine using any LLM you choose. GEOAssist has the following capabilities:

Literature reviews at scale: The tool can search the internet for scientific PDFs, read them automatically, judge their relevance, and use them to find more search terms. GEOAssist can download and analyse hundreds of papers, and then produce summaries with references, trends, and bibliographies.

Knowledge Graphs: By extracting geological terms and relationships from papers, GEOAssist can build a “map” of the connections between concepts, places, and processes, helping to reveal patterns that may be missed in manual reading.

Data extraction and map-based visualisation: GEOAssist can pull structured data from public geoscience databases (such as EarthByte GPlates, Macrostrat, and Mindat) and turn it into map outputs.

By releasing the GEOAssist source code, I aim to encourage experimentation, offer a glimpse of what is possible with LLMs, and enable others to build upon its capabilities—all while ensuring users retain control of their data. Geoscientists globally have already expressed interest in using and modifying the source code.

Geoscience reshaped

AI is fundamentally reshaping aspects of geoscience practice, with traditional tasks like literature searching and data gathering becoming increasingly automated and with AI tools used to help ideation. Value is shifting toward hybrid geoscience–AI skills: creating geologically informed prompts, validating AI outputs, and orchestrating human–AI workflows. This evolution arguably mirrors previous transitions, such as from hand-drawn maps to gridding and GIS, and it brings new mental tasks for geoscientists including information verification, decisions around applicability, and continually overseeing AI processes.

Professional practice may split between geoscientists who leverage AI effectively and those who don’t, and will require new competency standards, ethical frameworks, and education pathways. Documents offering guidance and best practise for professional geoscientists are already emerging (Geoscientists Canada, 2025).

Educational institutions must continue to balance teaching foundational geological reasoning with AI integration, like calculators in mathematics. Students need core geoscience skills while developing AI literacy to remain competitive.

We should encourage LLM experimentation in this fast-moving space for saving time and enhanced creativity. However, AI literacy isn’t just technical, it’s a mindset: curious, critical, responsible, distinguishing misinformation and identifying opportunities. We must question these tools and know when they help, when they harm, and when they shouldn’t be used at all.

Overconfidence could impact critical thinking, and there is some research showing increased use of AI leads to cognitive offloading, passing mental tasks to external systems (Gerlich, 2025; Lee et al., 2025). Of course, humans have always done this – from the clay tablets used by the Sumerians of Mesopotamia (creators of the world’s first urban civilizations), which served as one of humanity’s earliest tools for shifting mental tasks from memory into external storage, to present-day Google searches. However, AI tools now write, reason and recommend for us, not just remember. A balanced approach is therefore essential. Reading with a debate mindset encourages active engagement, anticipating counterarguments, examining evidence carefully and connecting ideas deeply. This critical approach improves retention and understanding.

In September 2025, a report from the Geoethics Commission of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) was published that presents recommendations for the ethical application of AI in the geosciences (Cleverley et al., 2025). Initiated after several high-profile ethics failures, the report is intended as a guide for practicing academic, industry, governmental and non-governmental geoscientists, society leaders, and policymakers, and was reviewed and approved by 22 experts from 14 countries over six continents. The recommendations cover areas such as transparency and explainability, bias and fairness, scientific integrity, environmental impacts, and geopolitics.

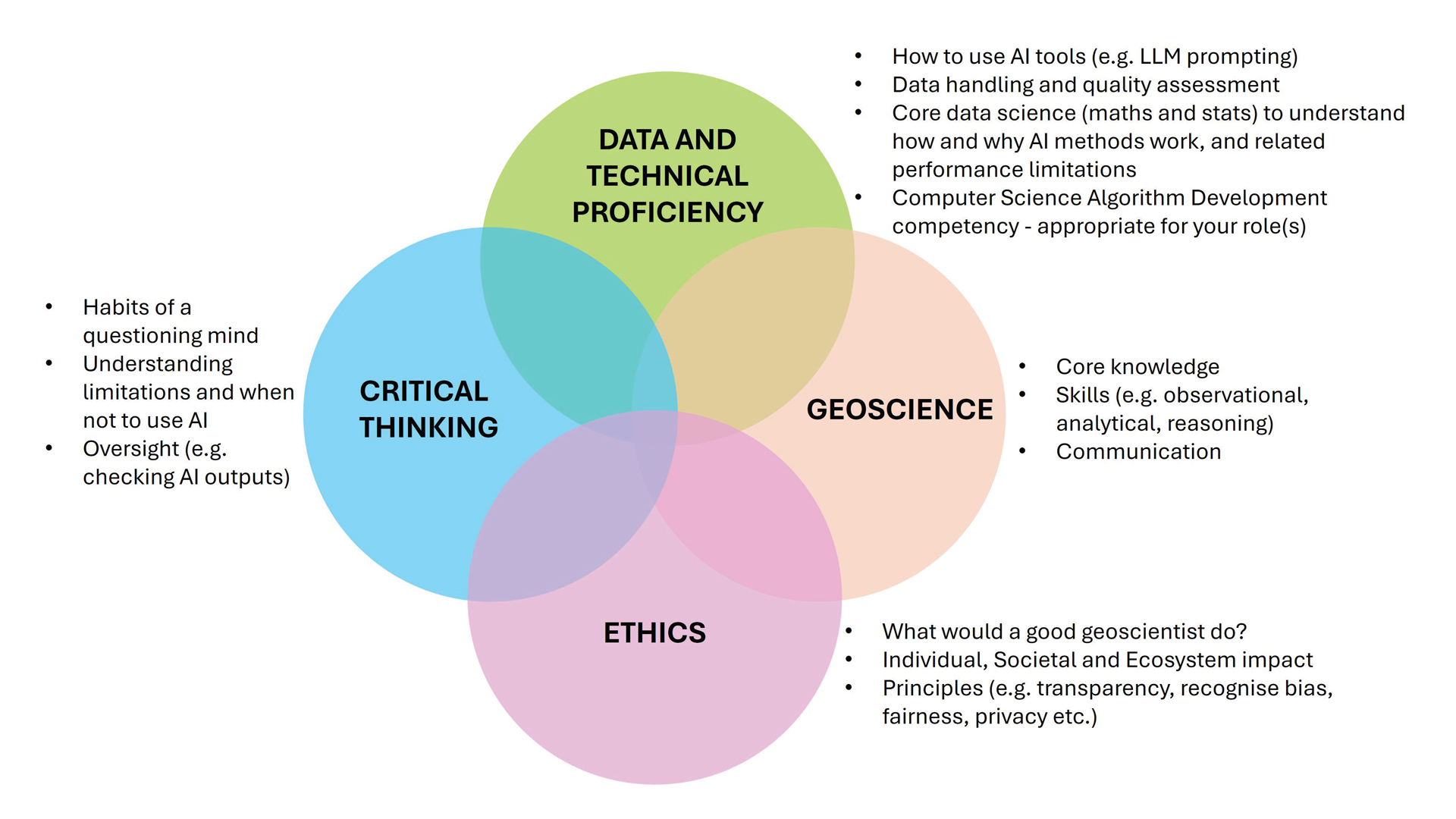

With these recommendations in mind, I propose an AI-literacy model (Fig. 3) that combines geoscience knowledge, ethics and critical thinking with data and technical proficiency. The model blends computational geosciences with AI education and societal impacts. This holistic and pragmatic approach towards the use of generative AI recognises core competencies, limitations and risks, whilst realising the benefits in an ethical manner.

Figure 3 | A model for AI literacy in the geosciences

A pragmatic approach

As geoscientists we should balance caution and scepticism with experimentation for LLM use and continue to develop AI-literacy mindsets. We must question how AI shapes geoscience knowledge, remain alert to its limits, and choose when, not only how, to use it. With a pragmatic approach, we can harness LLMs today to help deepen our understanding of Earth and better serve society, while preparing the next generation of geoscientists to thrive in an AI-augmented profession.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Peter Burgess, Professor of Computational Geoscience at the University of Liverpool, for his review of the AI literacy model shown in figure 3.

Prof Paul H Cleverley

Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland

Further reading

A full list of further reading is available at geoscientist. Online.

- Baucon, A. & de Carvalho, C.N. (2024) Can AI Get a Degree in Geoscience? Performance Analysis of a GPT-Based Artificial Intelligence System Trained for Earth Science (GeologyOracle). Geoheritage 16(121); https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-024-01011-2

- Bhattacharjee, B. et al (2024) indus: Effective and Efficient Language Models for Scientific Applications. arXiv Pre-print; https://arxiv.org/html/2405.10725v1

- Brown, C. (2025). UK’s AI adoption surges in daily life but lags behind in the workplace. EY AI Sentiment Index. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/en_uk/newsroom/2025/04/ey-ai-sentiment-index-2025

- Cleverley, P.H. (2025) GEOAssist: An autonomous geoscience LLM based agent; Retrieved from https://paulhcleverley.com/2025/08/30/opensource-geoassist-3-0-released-harness-the-power-of-natural-language-with-llm-driven-map-creation/

- Cleverley, P.H. et al. (2025) Artificial Intelligence (AI) Ethics Recommendations for the Geoscience Community. Task Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Geosciences of the Commission on Geoethics of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS). 26th September 2025; https://www.geoethics.org/_files/ugd/5195a5_5dcf66f87cca492c958319c3f4cdeffb.pdf

- Dubovik, A. & Suurmeyer, N. (2025) Testing Geological domain LLMs against benchmarks – Unlocking Conversations with your seismic data; Retrieved from https://zoom.us/rec/share/5F7qk0izPHgAT1i3pZm7DyUfQcD-3dWGqWG2vnmz5IcmxucqZt8BlzxiCMGunU3J.LnGl_yrHxfFcjAky

- Firth, J. R. (1957) Papers in linguistics. London: Oxford University Press.

- Geoethics (2025).Website of the Geoethics Commission of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS); Retrieved from https://www.geoethics.org/post/iugs-commission-on-geoethics-task-group-on-ai-in-geosciences

- Geoscientists Canada (2025) Usage of AI Tools for Professional Geoscientists in Canada; https://geoscientistscanada.ca/source/pubs/Insights%20into%20the%20Usage%20of%20AI%20Tools%20for%20Professional%20Geoscientists%20202509-%20Final.pdf

- Gerlich, M. (2025) AI Tools in Society. Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Societies 15(1); https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15010006

- Haarman, H. (2024) Enhance innovation by boosting idea generation with large language models; https://pubsonline.informs.org/do/10.1287/orms.2024.04.03/full

- Lee, H.P. et al. (2025) The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects from a Survey of Knowledge Workers. Proceedings of the Computer Human Interaction (CHI) 2025 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan. Article 1121, 1-22; https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713778

- Li, X. et al. (2023) Are ChatGPT and GPT-4 General-Purpose Solvers for Financial Text Analytics? A Study on Several Typical Tasks. arXiv Pre-print; https://arxiv.org/pdf/2305.05862

- Ma, Z. et al. (2024) Information Extraction from Historical Well Records Using a Large Language Model. arXiv Pre-print; https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.05438

- Mehmood, H. (2025) Leveraging large language models for floods mapping and advanced spatial decision support: A user-friendly approach with SATGPT. ITU Journal on Future and Evolving Technologies 6(1); https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/opb/jnl/S-JNL-VOL6.ISSUE1-2025-A05-PDF-E.pdf

- Meincke, L. et al. (2025) ChatGPT decreases idea diversity in brainstorming. Nature Human Behaviour 9, 1107-1109; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01953-1

- Morrison, S.M. et al. (2017) Network analysis of mineralogic systems. American Mineralogist 102(8), 1588-1596; https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2017-6104CCBYNCND

- Pantiukhin, D. et al. (2025) Accelerating Earth Science Discovery via Multi-Agent LLM Systems. arXiv Pre-print; https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.05854

- Smith, M. (2025) How are UK students really using AI? YouGov Survey; https://yougov.co.uk/society/articles/52855-how-are-uk-students-really-using-ai

- Stackoverflow (2025) 2025 Developer Survey; https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2025/ai

- Sufi, F.K. (2024) A framework for integrating GPT into geoscience research. Journal of Economy and Technology (In Press); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ject.2024.10.003

- Widlansky, M.J. & Komar, N. (2025) Building an Intelligent Data Exploring Assistant for Geoscientists. Journal of Geophysical Research: Machine Learning and Computation, 2(3); https://doi.org/10.1029/2025JH000649

- Yan, S. et al. (2025) AQUAH: Automatic Quantification and Unified Agent in Hydrology. arXiv Pre-print; https://www.arxiv.org/pdf/2508.02936