A Pebble in Time

As he prepares to donate his beloved copy of Gideon Mantell’s “Thoughts on a Pebble” to the Geological Society, Jonathan Bujak reconstructs the provenance of this rare literary gem

Thoughts on a Pebble. Front cover and title page. Gideon Mantell first published Thoughts on a Pebble in 1831 as a slim 18-page book. The published dedication in this sixth edition, which was published in 1842, is to his elder son, Reginald Neville Mantell, but some accounts suggest it was inspired by conversations with his younger son, Walter, about a flint pebble found in a nearby stream. (© Jonathan Bujak)

Gideon Mantell first published Thoughts on a Pebble in 1831 as a slim 18-page book based on answers he gave to his young son about a flint pebble found in a nearby stream. Strangely, there is no surviving record of the second through fifth editions. The sixth edition, published in 1842, was expanded to 43 pages, while the final, eighth edition, published in 1849, runs to 102 pages.

It is the sixth edition that I hold in my hands. I open the book — as always, with a feeling of wonder — but also with sadness, knowing we will soon be parted. Now in my late seventies, I will take the book to Burlington House to entrust it to a new protector, the Geological Society of London, so that this gem can be preserved and appreciated by future generations.

Inside, the book bears various inscriptions, written in three different hands. Before parting with it, I need to dig deeper into its history. Can I trace the journey of this slim volume through time using the handwritten inscriptions on its first pages?

From dinoflagellates to dinosaurs

I found my copy of Thoughts on a Pebble in a London bookshop in the 1970s. Having recently finished my PhD at the University of Sheffield, describing dinoflagellate (a type of phytoplankton) cysts from the Eocene Barton Beds of the Isle of Wight, I was first attracted to the illustrations of “Fossil Animalcules in Flint” — Mantell’s observations of microscopic fossils revealed after striking a fragment off a pebble and preparing a thin section for examination. Mantell’s drawings closely resembled Cretaceous and Paleogene species I had seen in the literature, with the relationship being confirmed by William Sarjeant in 1992 (Sarjeant, 1992).

These microfossils — initially described as fossil hystrichospheres and Xanthidia in the 19th century — remained a palaeontological puzzle for decades. It wasn’t until the 1960s that Stanford University’s William (Bill) Evitt identified them as the cysts of dinoflagellates.

Left: Illustration of “FOSSIL ANIMALCULES IN FLINT” in Thoughts on a Pebble, possibly drawn by Gideon Mantell’s wife, Mary. An opening is discernible in illustration 5, corresponding to the archeopyle that enables exit of the cellular contents from dinoflagellate cysts (© Jonathan Bujak). Right: Highly resistant fossilisable dinoflagellate cysts are formed inside the motile thecae which are not fossilised. The arrangement and size of the thecal plates (tabulation) have high taxonomic value and are reflected by the position of the cyst’s spines (processes) and archeopyle (© Geological Survey of Canada; images provided by Rob Fensome and Graham Williams, from an original drawing by William Evitt).

Formed when the motile cell (theca) contracts into a dormant stage, the cysts often bear elaborate appendages that reflect the plate configuration — or tabulation — of the parent theca. Thecae themselves, being composed of cellulose, are rarely preserved in the fossil record. The cysts, however, endure thanks to their walls of highly resistant organic material, similar to the walls of pollen and spores.

These resilient microfossils, and the remains of spores and pollen, are a cornerstone of palaeopalynology, providing high-resolution dating and environmental reconstructions of both marine and non-marine deposits. In some cases, millions of specimens can be recovered from just a few grams of sediment — a dense record of ancient seas and climate shifts, encapsulated in structures smaller than a grain of sand.

But not all dinos are microscopic.

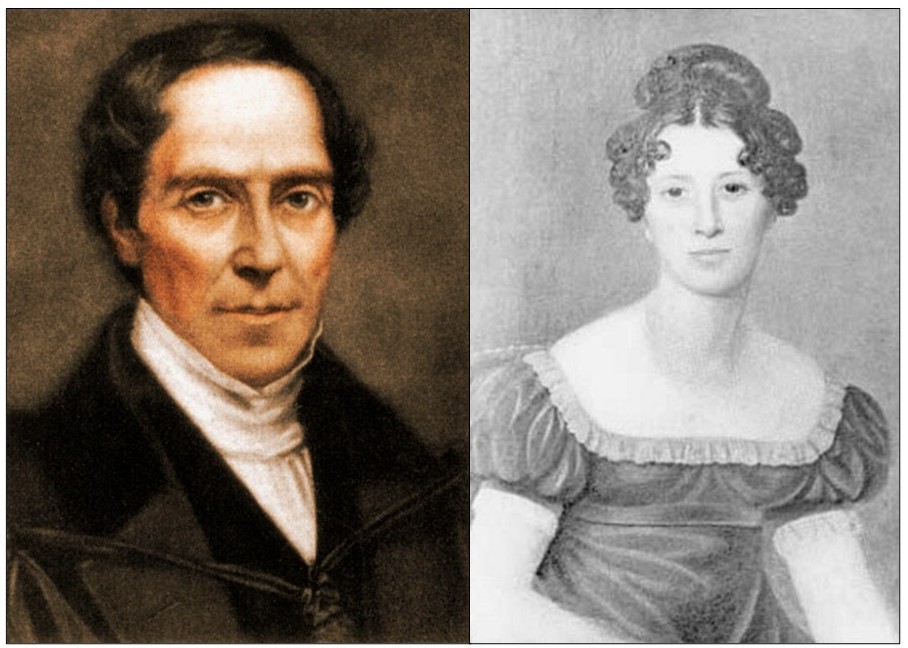

Gideon Mantell was a medical doctor who is best known for the fossils he found in the chalk and clay of southern England, visiting quarries and roadside exposures, often accompanied by his wife, Mary (née Woodhouse).

Portraits of Gideon and Mary Mantell (née Woodhouse) (images in Public Domain).

Recalling his discovery of an Iguanodon tooth, Mantell wrote on page 226 of his 1851 book, Petrifactions and Their Teachings:

“The present section will be devoted to the consideration of the structure and physiology of the colossal reptile . . . which is, perhaps, the most extraordinary, both in regard to its history and organization, of the saurians included in the Dinosaurian order the IGUANODON. The remains of this stupendous reptile that have been collected since my first discovery of a tooth in the quarry near Cuckfield, are very numerous, and comprise a considerable portion of the skeleton; but no part of the cranium has yet been recognised.”

Then on page 228:

“DISCOVERY OF THE IGUANODON. Soon after my first discovery of bones of colossal reptiles in the strata of Tilgate Forest, some teeth of a very remarkable character particularly excited my curiosity, for they were wholly unlike any that had previously come under my observation; even the quarrymen accustomed to collect the remains of fishes, shells, and other objects imbedded in the rocks, had not observed fossils of this kind; and until shown some specimens which I had extracted from a block of stone, were not aware of the presence of such teeth in the stone they were constantly breaking up for the roads.”

Mantell believed that the fossil tooth he had discovered came from an herbivorous reptile, but it was initially dismissed as the tooth of a wolf fish or the incisor of a rhinoceros when he presented it at a meeting of the Geological Society in 1822. In June 1823, Charles Lyell took the specimen to Paris and showed it to Georges Cuvier during a soirée. Cuvier initially dismissed it as a rhinoceros tooth (see Mantell’s Petrifactions and their Teachings, pp. 228–230); although he reconsidered his opinion the next day (Darwin Online, 1863; GBIF, 2023).

Mantell initially proposed the name Iguanosaurus

Seeking modern analogues, Mantell visited the Royal College of Surgeons in September 1824. There, assistant curator Samuel Stutchbury noted a resemblance between the fossil tooth and those of a modern iguana he had recently prepared. Mantell initially proposed the name Iguanosaurus in a letter to William Daniel Conybeare on 13 November 1824, but on 24 November 1824, Conybeare cautioned that the name was too similar to that of the living iguana. He instead suggested Iguanoides (“iguana-like”) or Iguanodon (“iguana-tooth”) — the latter being the name Mantell ultimately adopted (Dean, 1999; Simpson, 2015).

The Iguanodon tooth was later brought to New Zealand by Gideon Mantell’s son, Walter. A keen natural scientist, Walter gave the tooth pride of place, with this inscription, when the Colonial Museum (now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) opened in 1865 (Te Papa Museum, 2025):

A worn Iguanodon tooth from Cuckfield, Sussex, illustrated by Mantell in 1827, 1839, 1848 and 1851. . . This is the very tooth which Baron Cuvier first identified as a rhinoceros incisor on the evening of 28 June 1823. (Yaldwyn et al., 1997).

Mantell’s fossil Iguanodon tooth (circa 132-137 million years ago) found in Cuckfield, Sussex and curated at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Credit: Gift of the Mantell Family, 1930. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Te Papa (GH004839); Te Papa Museum, 2025).

Though the term “dinosaur” would not be coined until 1842 by Richard Owen, Mantell’s discoveries, including Hylaeosaurus and other giant reptiles, were among the earliest fossils to challenge conventional understanding of Earth’s biological past. His fossil finds — like his flint pebble — offered a new way of thinking about time, extinction, and the dramatic shifts in life on Earth.

The golden age of geology

Mantell’s revelations and those of his contemporaries captured the Victorian imagination in this ‘golden age of geology’. Mary Anning, William Buckland, George Cuvier, Charles Lyell, Roderick Murchison, Adam Sedgwick and William Smith (to name just a few) opened the door to an amazing world, with other pioneering women “forming a framework of assistants, secretaries, collectors, painters, and field geologists to the leading figures in the geological sciences, thereby adding to, and shaping their work” (Kölbl-Ebert, 2002).

The notion that Earth had once been dominated by giant, reptilian creatures — now long extinct — was both thrilling and unsettling. These “antediluvian monsters”, as they were often called, challenged biblical chronology and suggested a world far older, and stranger, than previously believed.

Mantell’s career was shadowed by rivalry

Yet despite his scientific brilliance and prolific discoveries, Mantell’s career was shadowed by rivalry — most notably with Richard Owen, the anatomist who founded and was the first Director of London’s Natural History Museum. Owen coined the term “Dinosauria” in 1842, grouping together Iguanodon, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus under a single grand order. While this was a pivotal moment in vertebrate palaeontology, Owen’s actions marginalised Mantell’s role. He downplayed Mantell’s contributions and even took credit for some of his discoveries, positioning himself as the authoritative voice of this emerging science.

The two men embodied contrasting paths: Mantell, a self-taught provincial doctor with a gift for observation and a deep passion for fossils; Owen, a metropolitan insider with political savvy and institutional backing. While Owen ascended to public prominence and royal favour, Mantell’s life became increasingly difficult — marked by chronic pain following a spinal injury, financial struggles, and professional isolation, described with great sensitivity in Deborah Cadbury’s book The Dinosaur Hunters (Cadbury, 2010).

Still, Mantell continued to write, lecture, and collect, driven by a conviction that fossils were more than curiosities — they were the keys to reconstructing ancient worlds. His popular works, including The Wonders of Geology and Thoughts on a Pebble, reflect this commitment to both science and public understanding. In many ways, he helped lay the foundation for palaeontology as a discipline, not through institutions, but through imagination and dedication.

A book passed through time

The cover of my copy of Thoughts on a Pebble is embossed green cloth with gold writing, encircled by a ring of leaves and berries resembling a laurel wreath. Worn by ancient Romans as a symbol of triumph, the laurel traces its roots to Greece and the god Apollo, patron of poetry, music, and athletics. The same wreath became a symbol of scholarly achievement in universities such as Italy’s Padua, where the academic tradition of the laurea may have originated.

Inside the wreath, in gold, are the words: Thoughts on a Pebble by Dr Mantell. There is some minor scuffing at the top and bottom of the spine and a small ink stain, but the inside of the book is pristine — complete with delicate tissue guards opposite colour illustrations.

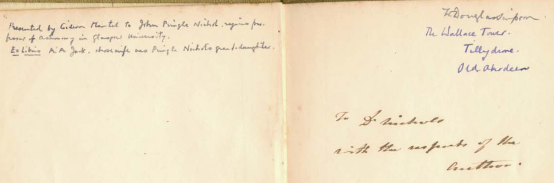

The first two pages are blank, except for several inscriptions, written in what appear to be three different hands.

The book’s inscriptions written in what appear to be three different hands. Left: Presented by Gideon Mantell to John Pringle Nichol, Regius Professor of Astronomy, University of Glasgow. Ex Libris A.A. Jack, whose wife was Nichol’s granddaughter. Top right (in the same hand): Dr Douglas Simpson. Below (in a different hand and fresher royal blue ink): The Wallace Tower, Tillydrone, Old Aberdeen. Bottom right (in bold, italic hand): To Dr Nichol with the respects of the author. [Or possibly: To Dr Nichols with the respects of the author.] (© Jonathan Bujak)

The inscription on the lower right-hand page, written in bold, italic hand, seems oldest:

To Dr Nichol with the respects of the author.

Comparison of the handwriting in this inscription with letters written in 1823 and signed by Gideon Mantell (which are available via a private auction site) shows that they were almost certainly written by Mantell himself.

But what is the story behind the other entries? The handwriting styles, ink colours, and careful inscriptions tell a story of stewardship — of a book not merely stored but cherished. As I followed the trail, I found that Thoughts on a Pebble had passed through the hands of astronomers, authors, antiquarians, suffragists, and scientists — a lineage as remarkable as the book itself.

The book’s provenance

The inscription on the left-hand page reads:

Presented by Gideon Mantell to John Pringle Nichol, Regius Professor of Astronomy, University of Glasgow.

Ex Libris A.A. Jack, whose wife was Nichol’s granddaughter.

It is written in the same hand as the inscription written on the top right that reads:

Dr Douglas Simpson

Both were presumably written by Simpson, but how did Simpson come to obtain the book and what else do these inscriptions tell us about the book’s provenance?

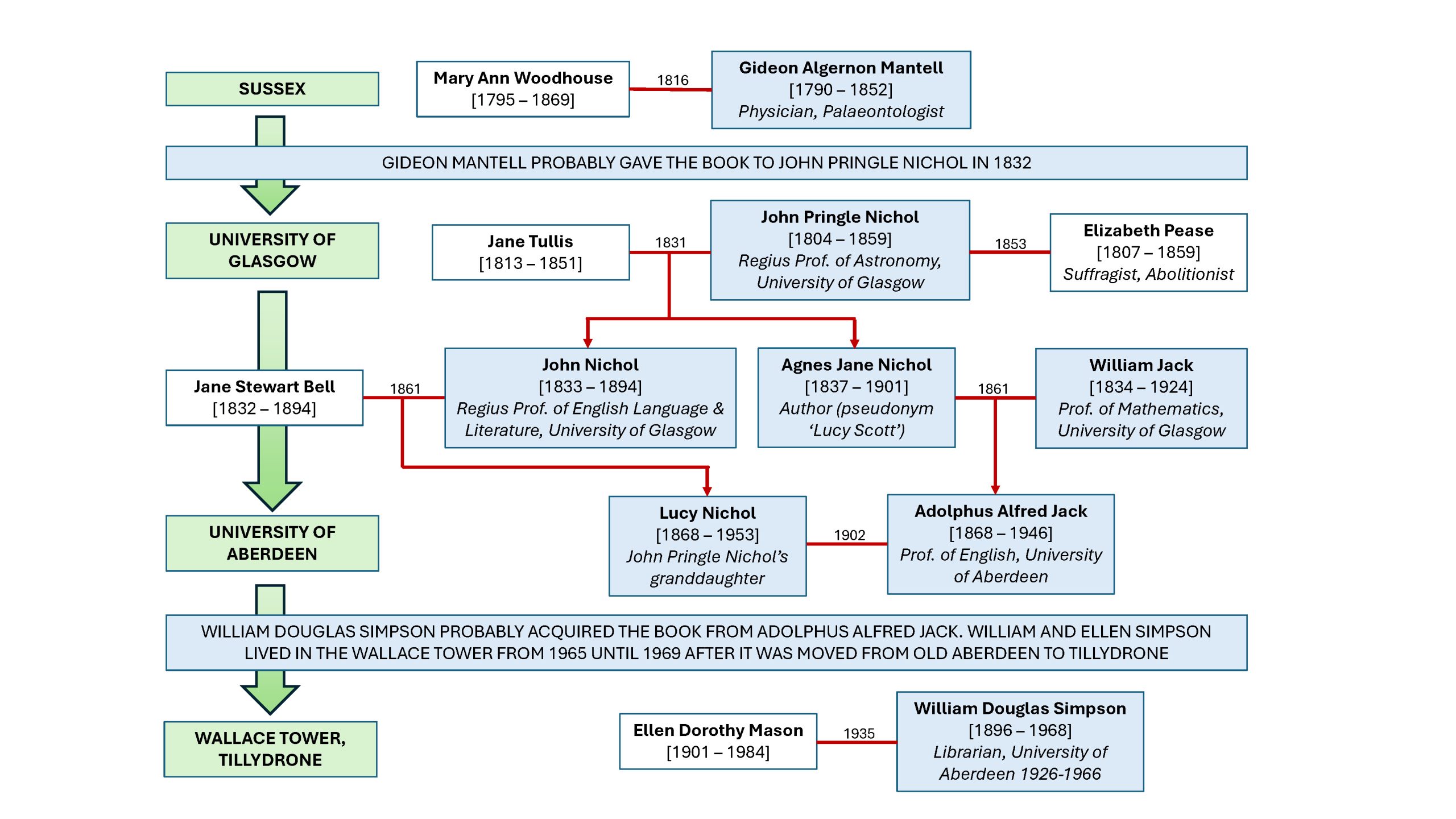

In their inscriptions, both Mantell and Simpson refer to John Pringle Nichol, Regius Professor of Astronomy at the University of Glasgow and a leading public communicator of science in Victorian Britain, implying that Mantell originally gave this book to John Pringle Nichol.

A friend of Sir William Hamilton and correspondent of John Stuart Mill, Nichol popularised nebular theory and wrote influentially on the plurality of worlds. He would almost certainly have crossed paths with Mantell because Nichol was also interested in geology. According to the Geological Society of London’s membership indexes, Nichol was elected a Fellow (proposed by Roderick Murchison) on 24 February 1841, but his election was declared void at the Council Meeting of 5 February 1845 because he never replied to the notice informing him of his election (The Geological Society, 1845, 1841).

In 1853, Nichol married Elizabeth Pease, a Quaker reformer, anti-slavery campaigner, and suffragist. She had attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840 and was the founding secretary of the Darlington Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. Their marriage caused controversy within the Society of Friends, leading her to resign from the Quaker community — yet she remained a passionate advocate for abolition and women’s education. Pease married Nichol following the death of his first wife, Jane Tullis, with whom he had two children, John Nichol and Agnes Jane Nichol.

John Nichol (to whom Thoughts on a Pebble was probably then passed) was appointed Regius Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Glasgow in 1862 and became known for his literary criticism and philosophical writings. He was also one of the first to introduce American literature to British students. A man of deep learning and compassion, John Nichol served as both scholar and mentor.

Agnes Jane Nichol married William Jack, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Glasgow and formerly editor of the Glasgow Herald. Jack had a distinguished academic and literary career, and the couple fostered an intellectually vibrant home that blended scientific precision with literary curiosity. Under the pen name Lucy Scott, Agnes published two novels of Victorian fiction: Brother and Sister (1879) and A Passion Flower (1882). Her creative work — drawing on the emotional currents of family and society — adds a literary dimension to the book’s legacy.

John Nichol’s daughter, Lucy, probably inherited the book from her father

John Pringle Nichol’s grandchildren re-connected when Agnes and William Jack’s son, Adolphus Alfred (A. A.) Jack, married John Nichol’s daughter, Lucy, who probably inherited the book from her father. Adolphus Jack — affectionately known to his family as “Dolfie” — served as Professor of English at the University of Aberdeen from 1915 to 1938. His students recalled that he frequently opened lectures with poetry and invited honours students for tea, often accompanied by Mrs Jack, fostering a warm and intellectually stimulating atmosphere.

Adolphus Jack’s association with the University of Aberdeen explains the final inscription, which reads: The Wallace Tower, Tillydrone, Old Aberdeen. This refers to the home of Dr William Douglas Simpson who, as University Librarian at Aberdeen and a renowned antiquarian and architectural historian, probably acquired the book from Adolphus Jack. Dating from around 1610 and originally located at the junction of Aberdeen’s Netherkirkgate and Carnegie’s Brae, the Wallace Tower was “subject to an enforced move from the Netherkirkgate in 1965, to make way for a Marks and Spencer store. It was carefully reconstructed in Seaton Park under the expert supervision of renowned historian Dr Douglas Simpson” (Andonova, 2024).

The Wallace Tower at Netherkirkgate (left) looking towards St. Nicholas Church, probably late 18th century (Silver City Vault, 2025; image in Public Domain) and at Tillydrone (right) (Credit: Colin Smith / Wallace Tower / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Simpson and his wife, Ellen, moved into the Wallace Tower at its new location in June 1965, but the building fell into disrepair in 1969, when Ellen probably moved out following her husband’s death in1968. It then had several tenants and was eventually left vacant, becoming a “derelict monument” until the Tillydrone Community Development Trust fought to “breathe new life into the forlorn tower”, securing planning permission in 2017 to carry out refurbishment to turn it into a community café (Andonova, 2024). Their photographs show the derelict state of the building, including “a heaven for anyone with a tendency of being nosey”.

Nothing is known about the disposal of Simpson’s library, including his copy of Thoughts on a Pebble, and there is no indication that it was ever part of the University of Aberdeen’s library collections.

Simpson’s wife, Ellen, whom he married in 1935, died in 1984 and was buried next to him, perhaps taking answers to the questions about Mantell’s book with her to the grave.

this tiny book was cherished

How did the book end up in a London bookstore? Was it sold or auctioned after Simpson died, perhaps with other volumes in his library? Whatever the answer, it is evident that this tiny book was cherished and preserved because of its scientific and family significance: given by Gideon Mantell to John Pringle Nichol, then handed down to his son John Nichol, then to John’s daughter, Lucy, who married her cousin Adolphus Alfred (A.A.) Jack, who probably gave it to William Douglas Simpson.

The book’s remarkable provenance — from Mantell’s Sussex to Victorian Glasgow, from the Scottish Enlightenment to the book-lined study of a librarian-antiquarian in Aberdeen — trace a legacy that can now endure into the future.

The provenance of Thoughts on a Pebble with its journey via different custodians shown in blue and to different locations shown in green. Each custodian of the book and their spouses must have cherished it as an heirloom, for the book to have been preserved in pristine condition for more than 130 years.

An enduring legacy

Gideon Mantell’s name lives on, not just in history books, but in the fossil record. In 2007, a revision of the Iguanodon genus led to the renaming of one of its species as Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis in honour of Gideon Mantell’s pioneering work. The dinosaur, originally discovered near Atherfield on the Isle of Wight in 1914 by Reginald Walter Hooley, was found to be distinct from Iguanodon and now bears Mantell’s name in recognition of his contributions to palaeontology.

Today, the skeleton of Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis stands proudly in Hintze Hall at London’s Natural History Museum — a tangible reminder of Mantell’s enduring impact on the science he helped to shape, and the role that his wife, Mary, played in that ‘golden age of geology’.

Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis in Hintze Hall at London’s Natural History Museum. (Credit: Emőke Dénes, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

It feels fitting, then, that the book — having passed through such hands — should now return to the Geological Society of London, where Mantell was elected a member on 15 May 1818. He later served on the Society’s Council from 1841 to 1844 and again from 1847 to 1852, and in 1835 received the Society’s second-ever Wollaston Medal, its highest honour. As a Fellow of the Geological Society, I see this donation, not as the end of the book’s journey, but as the beginning of a new chapter — one in which it will continue to inspire, educate and quietly astonish.

And so, as I prepare to part with this remarkable book, it seems only fitting to let Gideon Mantell have the final word. On pages 36–39 of my copy of Thoughts on a Pebble, he writes:

“Here we must bring our ‘Thoughts on a Pebble’ to a close; but not without adverting to the pure and elevating gratification which investigations of this nature afford, and the beneficial influence which they exert upon the mind and character. In circumstances where the uninstructed and unenquiring eye can perceive neither novelty nor beauty, the mind imbued with a taste for natural science finds an inexhaustible source of pleasure and instruction, and new and stupendous proofs of the power and goodness of the Eternal!

Every rock in the desert, every boulder on the plain, every pebble by the brookside, every grain of sand on the sea-shore, is fraught with lessons of wisdom to him whose heart is fitted to receive and comprehend their sublime import. Amidst the turmoil of the world, and the dreary intercourse of common life, we possess in these pursuits a never-failing source of delight, of which nothing can deprive us — an oasis in the desert, to which we can escape, and find a home ‘wherever the intellect can pierce, and the spirit can breathe the air.’”

Author

Dr Jonathan Bujak

Palaeontologist, co-founder of the Azolla Foundation, and previously a research scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada and Petro-Canada International Aid Corporation.

Dr Bujak was also involved with the only two geological expeditions to the North Pole: The 1979 Lomonosov Ridge Experiment (LOREX) and the 2004 Arctic Coring Expedition (ACEX) that discovered the Eocene Azolla Event (when azolla repeatedly covered large areas of the Arctic Ocean and triggered the change from a greenhouse climate towards our icehouse world; e.g., Bujak, J. & Bujak, A. (2014) The Arctic Azolla Event. Geoscientist 24, 10-15 and Bujak, J. & Bujak, A. (2022) The Azolla Story. The Azolla Foundation. 451 pp). Together with environmental scientist Alexandra Bujak, Dr Bujak set up the non-profit Azolla Foundation to help mitigate the threats associated with population growth and anthropogenic climate change.

Further reading

- Aberdeen Archives (1971) Wallace Tower, Tillydrone; https://emuseum.aberdeencity.gov.uk/objects/75005/wallace-tower-tillydrone (Accessed: 23 July 2025).

- Andonova, D. (2024) Exclusive: Inside Aberdeen’s abandoned Wallace Tower as cafe dream begins to take shape. Press and Journal; https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/news/aberdeen-aberdeenshire/6460300/inside-wallace-tower-as-cafe-takes-shape/ (Accessed: 20 July 2025).

- Cadbury, D. (2010) The Dinosaur Hunters: A True Story of Scientific Rivalry and the Discovery of the Prehistoric World. Revised ed. London: Fourth Estate.

- Darwin Online (1863) Lyell, C. Life, Letters and Journals, Vol. 2. Edited by K. Lyell; https://darwin-online.org.uk/converted/Ancillary/1863_Lyell_A282.html

- Dean, D.R. (1999) Gideon Mantell and the Discovery of Dinosaurs. Cambridge University Press, pp. 96–97.

- GBIF (2023) Iguanodon Mantell, 1825; https://www.gbif.org/species/144102742

- The Geological Society of London (1841) Fellowship admission form, no. 1312 (Ref: GSL/F/1/4). London: Geological Society Archives.

- The Geological Society of London (1845) Minutes of the Council Meeting, 5 February 1845 (Ref: GSL/CM/1/6). London: Geological Society Archives.

- The Geological Society portrait and bust collection (2025) Portrait of Gideon Algernon Mantell (1790–1852). Geological Society of London; https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/the-library/online-exhibitions/the-societys-portrait-and-bust-collection/portrait-of-gideon-algernon-mantell/ (Accessed: 17 April 2025).

- Kölbl-Ebert, M. (2002) British Geology in the Early Nineteenth Century: A Conglomerate with a Female Matrix. Earth Sciences History 21, 3–25; https://doi.org/10.17704/eshi.21.1.b612040xg7316614

- Mantell, G.A. (1822) The fossils of the South Downs; or illustrations of the geology of Sussex. The Royal Collections Trust, London; https://www.rct.uk/collection/1090323/the-fossils-of-the-south-downs-or-illustrations-of-the-geology-of-sussex-gideon (Accessed: 17 April 2025).

- Mantell, G. (1823) Signed letter by Gideon Mantell (1790–1852), Geologist and Dinosaur Fossil discoverer. Private collection; https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/176797948246 (Accessed: 20 July 2025).

- Mantell, G. (1825) Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of Tilgate Forest, in Sussex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 115, 179–186; https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1825.0010

- Mantell, G.A. (1851) Petrifactions and their Teachings; or, Geology in its Simplest Form. London: Bohn, pp. 228–230.

- Sarjeant, W.A.S. (1992) Gideon Mantell and the ‘Xanthidia.’ Archives of Natural History 19, 91–100; https://doi.org/10.3366/anh.1992.19.1.91

- Silver City Vault (2025) Wallace Tower, Netherkirkgate; https://www.silvercityvault.org.uk/index.php?a=ViewItem&i=103&WINID=1753263532952 (Accessed: 23 July 2025).

- Simpson, M.I. (2015) Iguanodon: A History of the First Discovered Dinosaur. Deposits Magazine, 2 December; https://depositsmag.com/2015/12/02/iguanodon/

- Te Papa Museum (2025) Gideon Mantell Te Papa collection; https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/agent/25988 (Accessed: 20 July 2025).

- Yaldwyn, J.C., Tee, G.J. & Mason, A.P. (1997) The status of Gideon Mantell’s “first” Iguanodon tooth in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Archives of Natural History 24, 397–421; https://doi.org/10.3366/anh.1997.24.3.397

This inscribed, sixth edition of Gideon Mantell’s book, Thoughts on a Pebble, is now part of the Geological Society’s Rare Books Collection and is available to view in the Library at Burlington House.

The Society accepts the donation of this rare book with many thanks. For guidance on donating rare books to our collection, please visit: https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/the-library/archives-and-special-collections/rare-books/

Citation: Bujak, J. A pebble in time. Geoscientist 35 (4), 30-34, 2025. DOI: 10.1144/geosci2025-033